Automated driving: would you like regulations with that? | Keynote by Bern Grush

We talk often about automated driving technology, but too seldom about its governance and regulation.

Articles and studies regarding automated vehicles (AVs) for passengers and freight have been plentiful since 2005. Positive hype peaked around 2015. The range of articles and reports throughout this time frequently covered technical aspects and challenges of vehicle automation: sensors such as lidar and cameras, machine learning with its edge cases, human drivers and their attention lapses leading to crashes, and the frequently misleading repetitions of the five SAE levels of automation.

Half of this writing projected advantages such as enhanced safety, efficiency, traffic flow, accessibility, productivity, passenger comfort, and environmental benefits. The other half focussed on disadvantages such as user fears based on the safety record to-date, increased congestion from over consumption, infrastructure challenges, and concerns over jobs, privacy, data security and ethical dilemmas.

Regulators need to put their hands on the wheel

This wide variety of interests, expectations, and worries is testimony to the complexity of what vehicle automation promises and appears to imply. The problem is that the majority of this has been passive: What might happen? What might this technology do for us? To us? The bias toward passive observation and analysis based on scant evidence is because technology development is still actively progressing, making it harder to ask, proactively: What should we do? What regulations should we prepare?

While not suggesting that vehicle automation is fully ready, it is certainly getting closer: creeping toward the consumer, galloping toward the regulator. While not ready for deployment at scale, it is ready for comprehensive regulatory attention, and some of this in areas that have received little attention to date.

The Urban Robotics Foundation in collaboration with Andrew Miller of Hatch Ltd strive to redress this shortcoming in a newly published report: The Driverless Endgame: Policy and Regulation for Automated Driving.

Stop wondering, start preparing

Rather than suppose or try to time what might happen, we assumed throughout this report that many promised milestones will come to pass but without projecting when. Instead, we asked and suggested how governments could or should prepare. We asserted that the time to start is now.

We assumed that in the near future, significant numbers of vehicles will be permitted on roadways without an onboard driver, and at times with no one onboard on the way to a pick up. Indeed, this has already begun in small numbers in a couple of cities. A lot of eyes are on these projects.

We assumed that initial deployment will be in service fleets for passengers or freight. We grappled with issues such as amendments to rules of the road, harmonisation among adjacent jurisdictions, owner responsibilities for maintenance, and the digitalisation of all these rules and changes. For passenger service vehicles — if these fleets are to grow in scale — we noted requirements for loading and unloading, especially at the kerb as there would often be competition leading to queueing problems. Such problems would need to be managed in a way similar to the reservation of runways at airports. For this we pointed to draft technical standard ISO 4448, Intelligent Transport Systems—Public-area mobile robots and automated pathway devices.

We assumed that many privately owned vehicles will have automated driving systems (ADS) that will soon allow owner/drivers to turn over the dynamic driving task (DDT) to their vehicle for extreme stretches of driving without hovering over the wheel or pedals. We especially examined the liability issues of that “in between time” during which the ADS is taking over from, or surrendering control to, a human operator. We considered vehicle user requirements, training and licensing, enforcement, and emergency response. We considered after-market modifications as there will be a conflict between “right-to-repair” and the liability insurance coverage for the time during which an ADS is in control and its provider responsible.

We were certainly not the first to consider each of these, but we wanted to organise all of these issues – both for service fleets, and for private ownership — into a single, integrated view in order to bring attention to the gap between the vehicle automation that we seem to be on the verge of, and the motor vehicle regulations which remain significantly under addressed.

Recommendations

We see very complex regulatory and deployment governance challenges in areas where there has been mostly silence. We offered recommendations and solution approaches in each case. Our conclusion is that while most of the world focusses on the technology behaviour of several hundred vehicles currently struggling to perfect their automated driving systems, the far larger and at least equally complex problem of modified regulations and digitalisation of our current rules and structures for automobility is receiving far too little attention.

To address the numerous issues described in the report, we prepared policy analysis and recommendations. In total, we made 43 recommendations. Some of these may appear as novel, a measure of the lag between the technology progress (and promises) and the actual state of regulations and governance.

Today, safety concerns rightfully press the brakes on automated driving. But even as those are resolved, a heavy foot will remain on the brakes until a considerable number of regulatory issues are addressed. For this, we recommended a dedicated office within each jurisdiction to prepare the required regulatory and oversight changes.

Public-area mobile robots and the Urban Robotics Foundation

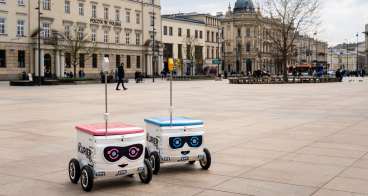

One chapter of our report particularly stands out. It addresses the integration of public-area mobile robots (PMRs), as described and researched by the Urban Robotics Foundation. PMRs include robotic systems for maintenance, security and last mile delivery within active transportation networks. The principal instances of these networks are pavements/sidewalks, bicycle lanes, and pedestrian passage ways in public buildings. Such facilities are often far less “structured” than are motorways.

Much is similar, and much is different between PMRs and AVs; critically, we are unprepared for governance in either case. The good news is an important number of common issues are evident. If regulators are smart, they will not need to do everything twice.

Any jurisdiction that will permit these devices will have to contend with things such as new bylaws, certification, licensing, machine behaviours, enforcement, multi-fleet orchestration, and monetisation. Small, single-fleet pilots will be easy. Extensive, multi fleet deployments will not be. Social media and YouTube are full of the former, but innovators and investors are preparing for the latter. Municipalities need to start preparing and regulators need to prepare those municipalities.

Bern Grush is the Executive Director of the Urban Robotics Foundation (URF), project leader for draft ISO 4448, and principal author of the forthcoming Municipal Guide to Public-area Mobile Robots. URF is a global non-profit organisation funded by memberships, guidebook sales, and educational workshops. Members of URF review drafts of the ISO Standard and the URF Guide. Membership is open to municipal, urban and traffic planners, accessibility advocates, large facility operators, technology companies, fleet operators, and researchers.

Published on 10 July 2023.